THE SURFBOAT EVOLUTION

Surfboats while an Aussie icon are common in New Zealand, South Africa and Britain. They are also appearing in some European countries. Dories have a strong history of rescue and racing in the United States by two rowers each using two oars (sculls). Gigs are raced in many countries including Britain, France and the Scilly Isles. They commonly have six rowers and a seated steersman. Gigs were originally raced out of coastal towns to win the right to pilot commercial sailing ships into small, treacherous ports. Gig, dory and surfboat racing has evolved from traditional rescue craft with a strong culture of saving people in peril.

Whaling longboats with a sweep oar and pilot boats built in the nineteenth century appear to be the origins of the rowed surf rescue craft we are familiar with. There is a rich tradition of oared lifeboats of the RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institute) performing gallant rescues around Britain. Similar rescue craft operated in parts of the US. In Cape Cod and other areas they were launched off beaches. The awe inspiring and bewildering bravery of these people who challenged the worst sea conditions was well known in the early 1900s.

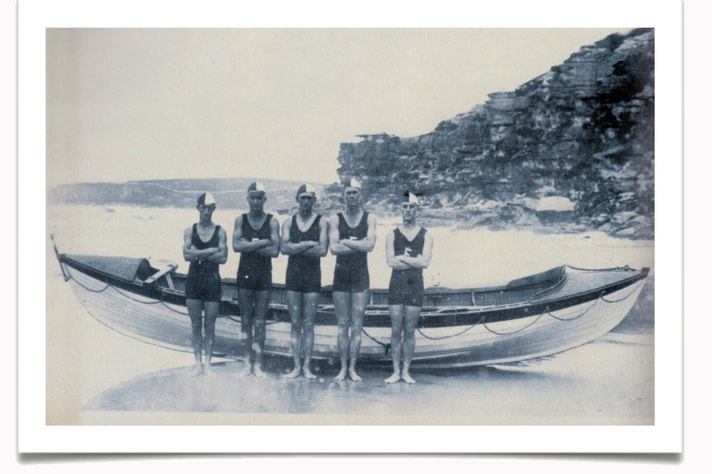

In Australia the Sly Brothers are claimed to be the first to introduce a boat for

surf rescue at Manly Beach from 1895. They started with a small fishing row boat and eventually used a double ended ship’s lifeboat.

The first Australian purpose built surfboat, ‘Surf King’, is claimed to have been designed in 1906 by Bronte member Walter Biddell. It was a ‘catamaran type boat’ with kapok stuffed torpedo shaped tubes made of wood, tin and canvas. Biddell then made a more conventional double ended boat called ‘Albatross’ with buoyancy tanks.

In 1908 Clovelly (Little Coogee) won the first rough water race held at Manly carnival. Seven clubs competed in rowing boats borrowed from ships in the harbor.

A breakthrough came in 1911 when Fred Notting of Manly Life Saving Club designed a boat based on a Norwegian craft with substantial banana adding his own ideas and a quarter bar. The boat was built by Holmes of Lavender Bay.

Surfboats received a boost following a dramatic rescue of two youths off Long Reef in 1914 using a small rowing boat. Jack Taylor manned the oars and H. Duckworth of Maroubra bailed! Warringah Council provided 18 foot long (5.5 metres) banana boats, built by Holmes, to Freshwater, Dee Why, Collaroy, Narrabeen and Newport surf clubs. The stroke pair shared a seat in the 18 foot boats.

The first surfboat race with purpose built craft is claimed to have been held at the Freshwater carnival in 1915. It was won by Freshwater swept by Dick Matheson. Matheson dominated the scene in the early years. He spent a season at nearby North Steyne and influenced young Harold C. Evans, better known as ‘Rastus’.

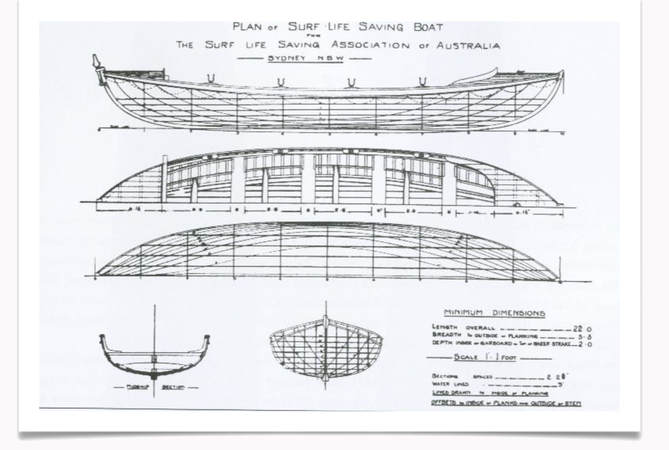

Charlie Proudfoot built a series of ‘Barracouta’ boats for North Narrabeen. Boats grew to 22-23 feet (6.7-7 metres) with a narrower beam. The Surf Life Saving Association then introduced standard measurements requiring the beam to be 5’3” (1.6 metres) wide. The earliest North Steyne boats were built by W. ‘Watty’ Ford at Berry’s Bay, Sydney. The second boat he made was a cedar carvel boat called ‘Bluebottle’. Cedar substantially lightened the boat’s weight compared to the boats made from kauri timber.

Whaling longboats with a sweep oar and pilot boats built in the nineteenth century appear to be the origins of the rowed surf rescue craft we are familiar with. There is a rich tradition of oared lifeboats of the RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institute) performing gallant rescues around Britain. Similar rescue craft operated in parts of the US. In Cape Cod and other areas they were launched off beaches. The awe inspiring and bewildering bravery of these people who challenged the worst sea conditions was well known in the early 1900s.

In Australia the Sly Brothers are claimed to be the first to introduce a boat for

surf rescue at Manly Beach from 1895. They started with a small fishing row boat and eventually used a double ended ship’s lifeboat.

The first Australian purpose built surfboat, ‘Surf King’, is claimed to have been designed in 1906 by Bronte member Walter Biddell. It was a ‘catamaran type boat’ with kapok stuffed torpedo shaped tubes made of wood, tin and canvas. Biddell then made a more conventional double ended boat called ‘Albatross’ with buoyancy tanks.

In 1908 Clovelly (Little Coogee) won the first rough water race held at Manly carnival. Seven clubs competed in rowing boats borrowed from ships in the harbor.

A breakthrough came in 1911 when Fred Notting of Manly Life Saving Club designed a boat based on a Norwegian craft with substantial banana adding his own ideas and a quarter bar. The boat was built by Holmes of Lavender Bay.

Surfboats received a boost following a dramatic rescue of two youths off Long Reef in 1914 using a small rowing boat. Jack Taylor manned the oars and H. Duckworth of Maroubra bailed! Warringah Council provided 18 foot long (5.5 metres) banana boats, built by Holmes, to Freshwater, Dee Why, Collaroy, Narrabeen and Newport surf clubs. The stroke pair shared a seat in the 18 foot boats.

The first surfboat race with purpose built craft is claimed to have been held at the Freshwater carnival in 1915. It was won by Freshwater swept by Dick Matheson. Matheson dominated the scene in the early years. He spent a season at nearby North Steyne and influenced young Harold C. Evans, better known as ‘Rastus’.

Charlie Proudfoot built a series of ‘Barracouta’ boats for North Narrabeen. Boats grew to 22-23 feet (6.7-7 metres) with a narrower beam. The Surf Life Saving Association then introduced standard measurements requiring the beam to be 5’3” (1.6 metres) wide. The earliest North Steyne boats were built by W. ‘Watty’ Ford at Berry’s Bay, Sydney. The second boat he made was a cedar carvel boat called ‘Bluebottle’. Cedar substantially lightened the boat’s weight compared to the boats made from kauri timber.

Sydney northern beaches dominated the early years of surfboat competition. The Newcastle area produced good crews in the 1930s. Swansea SLSC narrowly beat Cronulla at the 1931-32 Australian Championships. Cronulla won the next three years.

Boat builder Humphries of Swansea produced boats with fine lines. Another Newcastle boat builder with an 80 year tradition, N & E Towns, became popular after producing boats for Frank Davis of Manly LSC. Other significant surfboat builders over the years have been Phillips, Miles, Barnett, Boyd and Kelly. Most boats today are built by Perry Surfboats, Clymer Surfboats and DKG Surfboats.

Boat builder Humphries of Swansea produced boats with fine lines. Another Newcastle boat builder with an 80 year tradition, N & E Towns, became popular after producing boats for Frank Davis of Manly LSC. Other significant surfboat builders over the years have been Phillips, Miles, Barnett, Boyd and Kelly. Most boats today are built by Perry Surfboats, Clymer Surfboats and DKG Surfboats.

SURFBOAT CONSTRUCTION

Surfboat building methods have changed dramatically over the years. The early double ended surfboats of the 1920s and 30s were heavy clinker boats with overlapping planks usually built of kauri. The early surfboats were known as ‘banana’ boats because of their curved keels.

Cedar boats constructed by the carvel method, with planks butting up to each other, became popular.

Surfboat building methods have changed dramatically over the years. The early double ended surfboats of the 1920s and 30s were heavy clinker boats with overlapping planks usually built of kauri. The early surfboats were known as ‘banana’ boats because of their curved keels.

Cedar boats constructed by the carvel method, with planks butting up to each other, became popular.

Famous boat builder Boyd Humphries from Swansea produced the first tuck stern surfboat for Caves SLSC, called the ‘Seaswan II’. In its first season 1946-47 it won the State Junior Title. Double enders were replaced in the 1950s by square tucked (tuck stern) boats. Some of the early square tucked boats were carvel built. Carvel construction gave way to a long period of cold moulded timber construction.

Cold moulded boats had three layers of cedar planks, 1/8 inch (3mm) thick by 4 inches (100mm) wide laid up over the framing. The outer and inner layer, in diagonally opposite directions, and central layer perpendicular to the keel. Glue was used between the layers with thousands of staples temporarily holding the planks in place. The staples had to be painstakingly removed by a small hand tool. The framing consisted of silver ash keel, stem, stringers and ribs. These were laid on an open timber framed mould ready for the planking. The framed mould could be adjusted to create slight changes to the hull.

There is a classic misconception that cold moulded timber boats were heavy compared to modern boats. They were in fact the same weight because the current specified minimum weight is based on the weight of the timber boats! I understand the modern boat with its high tech materials could be substantially lighter and still be structurally sound. However it may feel entirely different in the surf and wind.

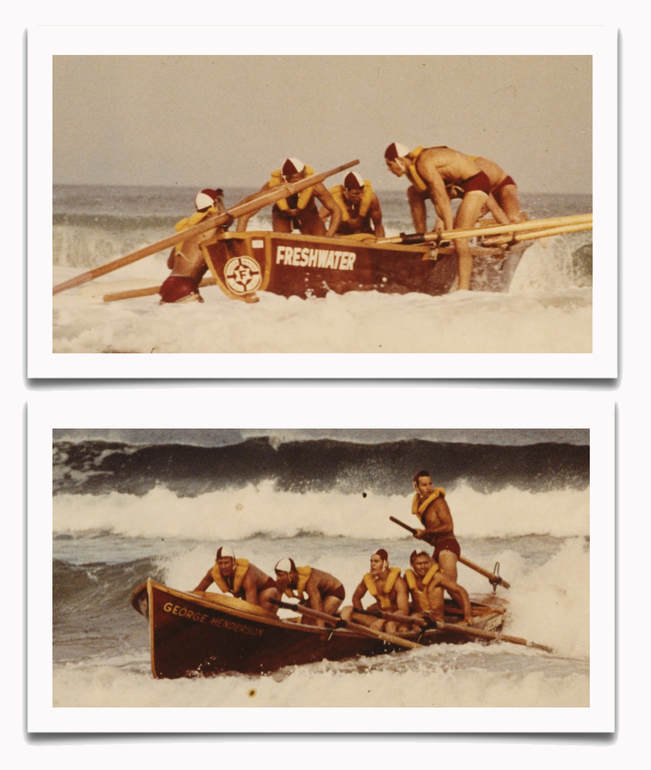

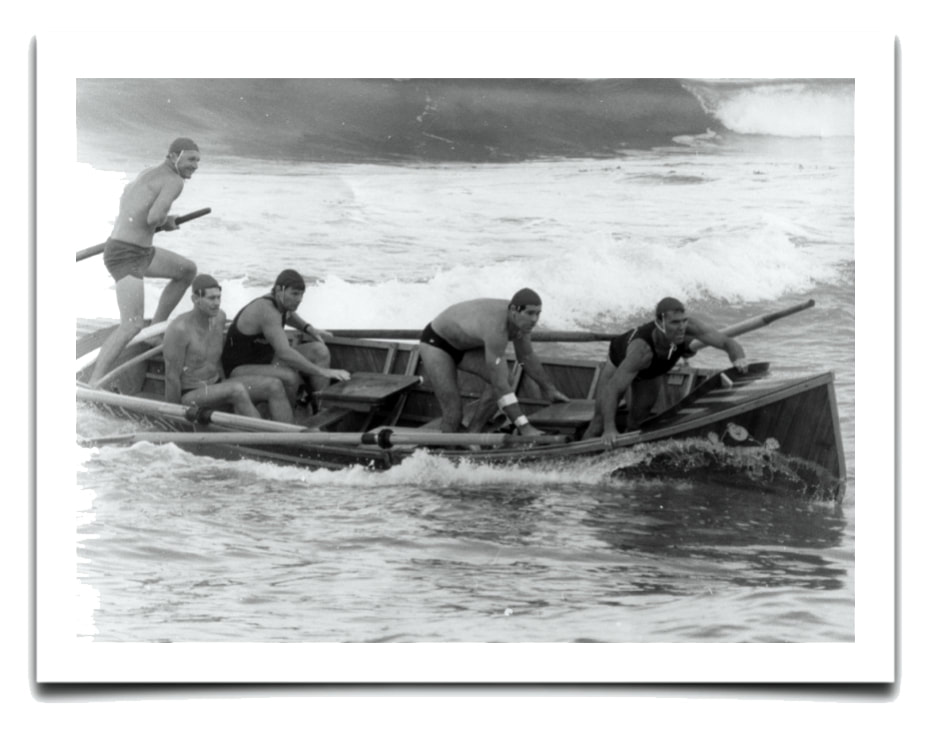

Reminiscences by current mature aged boaties go back to the open timber boats of the 1960s and 70s. There are even several old boaties that can recall rowing double enders. Most of the ones I know who claim to have rowed doble enders later joined march past teams so I am not sure whether their judgement can be relied upon!

After the introduction of square tucked boats and cold moulded timber construction there was a long period of little change. In fact the shape of the outer hull has changed little since the mid 1970s.

The bow and stern timber decking was sometimes decorated reflecting the boat builder’s skill and the club’s budget. Alternating diagonal stripes of light (ash) and dark (cedar) timber was popular. Bill Clymer sometimes applied his marquetry skill to special orders. Palm Beach boats often had a cabbage tree leaf inset in the bow deck.

One change during the 1970s occurred when the position of the bow and stroke rowlock was allowed to be built out from the gunwale. Before this change oars were different lengths depending on the seat position. The second stroke and second bow positions in the centre of the boat had the longest oars, hence the term ‘engine room’. The bow oar was shorter because the inside of the boat was narrower. The stroke oar was the shortest affectionately known as the ‘paddle pop stick’. Extending the bow and stroke rowlocks allowed a longer inboard length and because of the gearing concept, a longer out board length as well.

Cold moulded boats had three layers of cedar planks, 1/8 inch (3mm) thick by 4 inches (100mm) wide laid up over the framing. The outer and inner layer, in diagonally opposite directions, and central layer perpendicular to the keel. Glue was used between the layers with thousands of staples temporarily holding the planks in place. The staples had to be painstakingly removed by a small hand tool. The framing consisted of silver ash keel, stem, stringers and ribs. These were laid on an open timber framed mould ready for the planking. The framed mould could be adjusted to create slight changes to the hull.

There is a classic misconception that cold moulded timber boats were heavy compared to modern boats. They were in fact the same weight because the current specified minimum weight is based on the weight of the timber boats! I understand the modern boat with its high tech materials could be substantially lighter and still be structurally sound. However it may feel entirely different in the surf and wind.

Reminiscences by current mature aged boaties go back to the open timber boats of the 1960s and 70s. There are even several old boaties that can recall rowing double enders. Most of the ones I know who claim to have rowed doble enders later joined march past teams so I am not sure whether their judgement can be relied upon!

After the introduction of square tucked boats and cold moulded timber construction there was a long period of little change. In fact the shape of the outer hull has changed little since the mid 1970s.

The bow and stern timber decking was sometimes decorated reflecting the boat builder’s skill and the club’s budget. Alternating diagonal stripes of light (ash) and dark (cedar) timber was popular. Bill Clymer sometimes applied his marquetry skill to special orders. Palm Beach boats often had a cabbage tree leaf inset in the bow deck.

One change during the 1970s occurred when the position of the bow and stroke rowlock was allowed to be built out from the gunwale. Before this change oars were different lengths depending on the seat position. The second stroke and second bow positions in the centre of the boat had the longest oars, hence the term ‘engine room’. The bow oar was shorter because the inside of the boat was narrower. The stroke oar was the shortest affectionately known as the ‘paddle pop stick’. Extending the bow and stroke rowlocks allowed a longer inboard length and because of the gearing concept, a longer out board length as well.

Cold moulded boats were built by a small number of specialist surfboat builders as well as by some larger established wooden boat yards that made a variety of other craft. It became increasingly difficult to source quality timber. Silver ash used for its strength as keels, stringers and gunwales was a rainforest timber which became restricted as forestry practices became more enlightened. Cedar planking became scarcer and derivatives started being imported under the loose name ‘cedar’.

For a short time in the early 1980s the West System was introduced to surfboats where cedar planking or plywood strips were combined with fiberglass sheathing. In many craft this system had proven very durable but the forces exerted on surfboats by some adventurous crews challenged the composite construction method.

I understand the first fiberglass surfboat was made by Bob McClelland. He sourced the Clymer surfboat named ‘CAGA Finance’ that Freshwater’s open crew rowed to victory at the 1974 Australian Championships in Glenelg, South Australia. Possibly not the best boat to take a mould from as it had been rigged for flatter South Australian gulf conditions, with the seats being moved forward. Consequently it could be a little wet going through Sydney northern beaches waves! Penguin SLSC bought the boat at the 1974 Championships and took it back to northern Tasmania where it suited the conditions.

I understand the first fiberglass surfboat was made by Bob McClelland. He sourced the Clymer surfboat named ‘CAGA Finance’ that Freshwater’s open crew rowed to victory at the 1974 Australian Championships in Glenelg, South Australia. Possibly not the best boat to take a mould from as it had been rigged for flatter South Australian gulf conditions, with the seats being moved forward. Consequently it could be a little wet going through Sydney northern beaches waves! Penguin SLSC bought the boat at the 1974 Championships and took it back to northern Tasmania where it suited the conditions.

The fibreglass constructions also evolved with the introduction of better materials and methods. Surfboat manufacturers Miles, Ninham and Clymer all converted from timber construction to fiberglass. Today the boats are made using two moulds, one for the outer hull and one for the interior. A combination of fiberglass and foam are laid out and a vacuum bag placed over the loaded mould. Resin is infused into the vacuum bag. The hull is cured and removed from the mould. The outer and inner sections are then joined allowing the fitout to commence.

The change from timber to fibreglass surfboats made innovations to the hull more possible. I understand Gus Macdonald, a NSW south coast dentist was the first to internally fit an inner shell possibly about 1986 following variation to boat specification no. 457/86.

The inner shell design was quickly and enthusiastically accepted. The main advantage being the vastly reduced amount of water a boat could take on board when hit by a wave. Together with powerful pumps it was easier to recover from being swamped by a wave.

The downside of the inner shell was not considered by mainstream competitors nor the SLSA. I am not aware that anyone anticipated that there would be a dramatic increase in the number of rowers washed out of boats. The change in the buoyancy characteristics increased the likelihood of a boat suffering a backshoot. The fact that boats held much less water when hit by a wave clouded any disadvantages.

Once inner shells became the norm rowers could no longer take refuge in the open hull to lower the centre of gravity when broaching or when colliding with another boat. Nor could a rower seek the safety of the open hull in a rollover increasing the danger of being crushed by the gunwale in shallow water. Open surfboats simply sunk to the gunwales when filled with water on the way to sea. If an open boat was swamped while on a wave it lost momentum and did not continue out of control as current day tanked boats tend to do. Open boats on waves did not rollover as much because rowers could get down and lower the boat’s centre of gravity. Discarded rowers could easily get back to the boat and hang on to it.

The inner shell innovation created a trend with most Sweeps lessening their emphasis on taking a boat through the surf ‘dry’. We have witnessed numerous experienced rowers being washed out of surfboats at the Australian Titles held at Kurrawa in rough conditions. On a few occasions all 30 competitors in a six boat race were floating in the water awaiting rescue while their buoyant boats continued shoreward unmanned, leaving competitors with nothing to hang onto except the occasional oar! Few boaties are known for their swimming expertise! There is a big difference between passing an annual ‘proficiency’ run-swim-run test and trying to stay afloat in the second or third break at Kurrawa on a big day! Would the number of surfboat competitors needing to be rescued have been less with open boats is debatable? Unfortunately anyone expressing that view would be labeled a dinosaur before the debate even commenced. It is interesting to reflect how easily such a major innovation was introduced without understanding the full implications.

The change from timber to fibreglass surfboats made innovations to the hull more possible. I understand Gus Macdonald, a NSW south coast dentist was the first to internally fit an inner shell possibly about 1986 following variation to boat specification no. 457/86.

The inner shell design was quickly and enthusiastically accepted. The main advantage being the vastly reduced amount of water a boat could take on board when hit by a wave. Together with powerful pumps it was easier to recover from being swamped by a wave.

The downside of the inner shell was not considered by mainstream competitors nor the SLSA. I am not aware that anyone anticipated that there would be a dramatic increase in the number of rowers washed out of boats. The change in the buoyancy characteristics increased the likelihood of a boat suffering a backshoot. The fact that boats held much less water when hit by a wave clouded any disadvantages.

Once inner shells became the norm rowers could no longer take refuge in the open hull to lower the centre of gravity when broaching or when colliding with another boat. Nor could a rower seek the safety of the open hull in a rollover increasing the danger of being crushed by the gunwale in shallow water. Open surfboats simply sunk to the gunwales when filled with water on the way to sea. If an open boat was swamped while on a wave it lost momentum and did not continue out of control as current day tanked boats tend to do. Open boats on waves did not rollover as much because rowers could get down and lower the boat’s centre of gravity. Discarded rowers could easily get back to the boat and hang on to it.

The inner shell innovation created a trend with most Sweeps lessening their emphasis on taking a boat through the surf ‘dry’. We have witnessed numerous experienced rowers being washed out of surfboats at the Australian Titles held at Kurrawa in rough conditions. On a few occasions all 30 competitors in a six boat race were floating in the water awaiting rescue while their buoyant boats continued shoreward unmanned, leaving competitors with nothing to hang onto except the occasional oar! Few boaties are known for their swimming expertise! There is a big difference between passing an annual ‘proficiency’ run-swim-run test and trying to stay afloat in the second or third break at Kurrawa on a big day! Would the number of surfboat competitors needing to be rescued have been less with open boats is debatable? Unfortunately anyone expressing that view would be labeled a dinosaur before the debate even commenced. It is interesting to reflect how easily such a major innovation was introduced without understanding the full implications.

OARS

Oars have evolved from timber to carbon fibre. In the early days oars were carved out of a single piece of hardwood timber. The rowing blades were straight and quite narrow. Blades evolved curves and lighter timbers were incorporated.

In the later stages of timber oar manufacture few of us appreciated they had almost become scientific works of art. The centre of the shaft was hollow to lighten and help balance the oar inboard and outboard of the rowlock. At times a lead weight was placed inside the handle. A variety of timbers were used in particular parts of the oar based on the tensile and compressive forces the shaft had to endure. Timbers such as spruce, oregon and silver ash had specific weight and strength qualities. Oars could be made stronger without becoming too heavy by placing particular timbers in certain parts of the shaft.

The characteristics of individual timber oars could differ in the hands of strong rowers. Some might be quite whippy (flexible) while others were too stiff. A small amount of flexibility was preferred as it acted like a shock absorber on the forearms. The timber and glue lines in some oars caused them to dive during the stroke or shudder. Usually you accepted what was provided and learnt to adapt to any idiosyncrasies. Oars seldom felt the same after they were repaired. Our 1970s Freshwater crew was looked after by Bill Clymer who sometimes gave us up to six sets to trial. It is also an advantage when your brother in law is a specialist timber oar craftsman!

The section of the oar shaft that sat in the metal rowlock had a protective leather sleeve. A built up leather band (button) stopped the oar from slipping through the rowlock. The button became hard plastic and the leather sleeve was replaced by a durable plastic one.

There was an experimental period when aluminium shafted oars were trialled. They were as responsive as a length of water pipe and best forgotten about. Aluminium oars were much less successful than the aluminium hulled surfboats that a few clubs trialled, probably sponsored by Alcoa.

The high cost of making timber oars made it possible for carbon fibre shafted oars with fibreglass blades to be introduced. Initially we noticed carbon fibre oars were consistent and they were very stiff. Three different grades of shaft stiffness was introduced.

Timber sweep oars were commonly made from spruce. We are going through an evolving period as timber sweeps oars are steadily being replaced by carbon fibre sweep oars. Some Sweeps still prefer timber sweep oars for their flexibility. An advantage of carbon fibre sweep oars is the three piece construction allowing separate replacement of the handle, shaft or fiberglass blade.

One safety aspect of carbon fibre oars is the potential splintering effect when they break. I understand sheathing could safeguard against splintering related injury.

Oars have evolved from timber to carbon fibre. In the early days oars were carved out of a single piece of hardwood timber. The rowing blades were straight and quite narrow. Blades evolved curves and lighter timbers were incorporated.

In the later stages of timber oar manufacture few of us appreciated they had almost become scientific works of art. The centre of the shaft was hollow to lighten and help balance the oar inboard and outboard of the rowlock. At times a lead weight was placed inside the handle. A variety of timbers were used in particular parts of the oar based on the tensile and compressive forces the shaft had to endure. Timbers such as spruce, oregon and silver ash had specific weight and strength qualities. Oars could be made stronger without becoming too heavy by placing particular timbers in certain parts of the shaft.

The characteristics of individual timber oars could differ in the hands of strong rowers. Some might be quite whippy (flexible) while others were too stiff. A small amount of flexibility was preferred as it acted like a shock absorber on the forearms. The timber and glue lines in some oars caused them to dive during the stroke or shudder. Usually you accepted what was provided and learnt to adapt to any idiosyncrasies. Oars seldom felt the same after they were repaired. Our 1970s Freshwater crew was looked after by Bill Clymer who sometimes gave us up to six sets to trial. It is also an advantage when your brother in law is a specialist timber oar craftsman!

The section of the oar shaft that sat in the metal rowlock had a protective leather sleeve. A built up leather band (button) stopped the oar from slipping through the rowlock. The button became hard plastic and the leather sleeve was replaced by a durable plastic one.

There was an experimental period when aluminium shafted oars were trialled. They were as responsive as a length of water pipe and best forgotten about. Aluminium oars were much less successful than the aluminium hulled surfboats that a few clubs trialled, probably sponsored by Alcoa.

The high cost of making timber oars made it possible for carbon fibre shafted oars with fibreglass blades to be introduced. Initially we noticed carbon fibre oars were consistent and they were very stiff. Three different grades of shaft stiffness was introduced.

Timber sweep oars were commonly made from spruce. We are going through an evolving period as timber sweeps oars are steadily being replaced by carbon fibre sweep oars. Some Sweeps still prefer timber sweep oars for their flexibility. An advantage of carbon fibre sweep oars is the three piece construction allowing separate replacement of the handle, shaft or fiberglass blade.

One safety aspect of carbon fibre oars is the potential splintering effect when they break. I understand sheathing could safeguard against splintering related injury.

ROWLOCKS

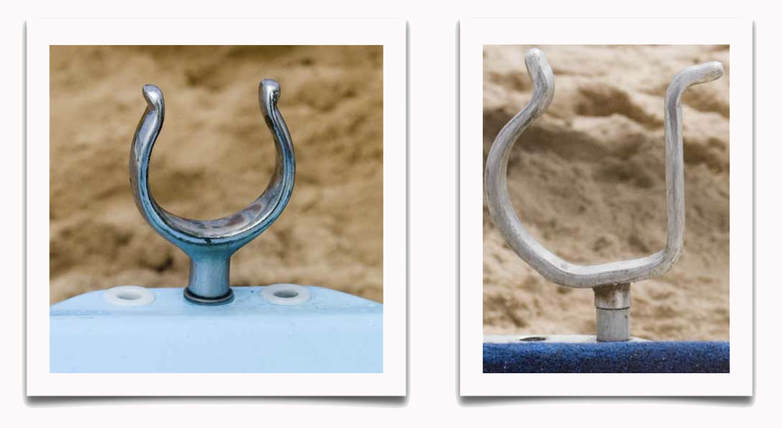

Rowlocks in early rowing boats were virtually just two vertical pegs. Early surfboats used vertical rowlocks that resembled the shape of a lyrebird tail. The oars did not have a retaining button so the rower had to control the amount of shaft inboard and outboard of the rowlock.

Quarter barring was a common practice when riding a wave in double ended boats. The stroke and second stroke would remove their oars from the rowlock and place them under the quarter bar. They stood and helped the sweep keep the boat straight by sweeping with their rowing oars. The underside of the quarter bar was curved outside the gunwale to hold the stroke oars. The early rowlocks made it easy for the oars to be removed.

Rowlocks evolved with an outwardly curved surface to minimize the surface area of the oar button against it. Suddenly rowers had to decide which way around the rowlock should be before the oar was inserted. Particularly in the late 1960s and 1970s the rowlock was angled above its shaft (pin) to reflect the angle of the oar shaft from the gunwale to the water. In more modern boats the rowlock shaft is already angled through the gunwale. Consequently a modern rowlock cannot be used in a 1970s surfboat! Something to bear in mind if you are restoring one!

Square back rowlocks became popular in stillwater shells and were adapted to surfboats. Surfers Paradise SLSC open boat crew swept by Ron Payne and stroked by stillwater champion Steve Evans used them when they became the first Queensland open surfboat crew to win an Australian Championship in 1989.

Nowadays round rowlocks have almost totally been replaced by square back rowlocks. Only a few crews at clubs such as Freshwater, Bilgola and Lorne still maintain the skill to use round rowlocks. The horse has bolted in an act of mass decision making resulting in the introduction of an item which is less applicable to surf conditions.

Square rowlocks preset the angle the blade enters the water and help maintain the angle through the water. This appears to be advantageous and there is no doubt they are easier to use, especially for our stillwater friends when they see the light and transfer to surfboats.

Square back rowlocks are applicable to flat water because the angle of the boat to the water surface is static. As surfboats rise longitudinally up and down in surf the angle of entry by the blade can dramatically change between each stroke. With a round rowlock a rower can slightly rotate the wrist to create the correct entry angle with the water. A predetermined square back rowlock cannot do this. The worst affected are the bow pair. Rowing round rowlocks requires the wrist and forearm muscles to be used more than with square back rowlocks.

Interestingly those who understand the simple logic of round rowlock advantages are usually considered to be out of date! Why?

Rowlocks in early rowing boats were virtually just two vertical pegs. Early surfboats used vertical rowlocks that resembled the shape of a lyrebird tail. The oars did not have a retaining button so the rower had to control the amount of shaft inboard and outboard of the rowlock.

Quarter barring was a common practice when riding a wave in double ended boats. The stroke and second stroke would remove their oars from the rowlock and place them under the quarter bar. They stood and helped the sweep keep the boat straight by sweeping with their rowing oars. The underside of the quarter bar was curved outside the gunwale to hold the stroke oars. The early rowlocks made it easy for the oars to be removed.

Rowlocks evolved with an outwardly curved surface to minimize the surface area of the oar button against it. Suddenly rowers had to decide which way around the rowlock should be before the oar was inserted. Particularly in the late 1960s and 1970s the rowlock was angled above its shaft (pin) to reflect the angle of the oar shaft from the gunwale to the water. In more modern boats the rowlock shaft is already angled through the gunwale. Consequently a modern rowlock cannot be used in a 1970s surfboat! Something to bear in mind if you are restoring one!

Square back rowlocks became popular in stillwater shells and were adapted to surfboats. Surfers Paradise SLSC open boat crew swept by Ron Payne and stroked by stillwater champion Steve Evans used them when they became the first Queensland open surfboat crew to win an Australian Championship in 1989.

Nowadays round rowlocks have almost totally been replaced by square back rowlocks. Only a few crews at clubs such as Freshwater, Bilgola and Lorne still maintain the skill to use round rowlocks. The horse has bolted in an act of mass decision making resulting in the introduction of an item which is less applicable to surf conditions.

Square rowlocks preset the angle the blade enters the water and help maintain the angle through the water. This appears to be advantageous and there is no doubt they are easier to use, especially for our stillwater friends when they see the light and transfer to surfboats.

Square back rowlocks are applicable to flat water because the angle of the boat to the water surface is static. As surfboats rise longitudinally up and down in surf the angle of entry by the blade can dramatically change between each stroke. With a round rowlock a rower can slightly rotate the wrist to create the correct entry angle with the water. A predetermined square back rowlock cannot do this. The worst affected are the bow pair. Rowing round rowlocks requires the wrist and forearm muscles to be used more than with square back rowlocks.

Interestingly those who understand the simple logic of round rowlock advantages are usually considered to be out of date! Why?

SEATS

The seat and rowing position has greatly evolved from the early days. Seats were originally narrow benches. The rower simply sat in one place and rowed using only the body and arm action. At some clubs such as Swansea Caves, rowers held the oar in an over and under hand fashion.

The replacement of the bench seat by a long fixed seat, allowed the rower to slide their backside up and down the seat. This enabled the legs to be used to help power the stroke and increased the length the blade travelled through the water. The stroke rate was substantially lower than the fast short strokes previously taken on non sliding bench seats. Most surfboat rowers slide along the seat by immodestly hitching up their costumes in “wedgy” fashion. The only lubrication used by the majority of rowers is sea water. Rolling seats are occasionally used in training or marathon events.

Seat heights have tended to become higher raising the centre of gravity. The boat may be a little less stable but this is offset by giving the rowers a stronger body position.

The seat and rowing position has greatly evolved from the early days. Seats were originally narrow benches. The rower simply sat in one place and rowed using only the body and arm action. At some clubs such as Swansea Caves, rowers held the oar in an over and under hand fashion.

The replacement of the bench seat by a long fixed seat, allowed the rower to slide their backside up and down the seat. This enabled the legs to be used to help power the stroke and increased the length the blade travelled through the water. The stroke rate was substantially lower than the fast short strokes previously taken on non sliding bench seats. Most surfboat rowers slide along the seat by immodestly hitching up their costumes in “wedgy” fashion. The only lubrication used by the majority of rowers is sea water. Rolling seats are occasionally used in training or marathon events.

Seat heights have tended to become higher raising the centre of gravity. The boat may be a little less stable but this is offset by giving the rowers a stronger body position.